Memento Screenplay Analysis | Innovating Stories

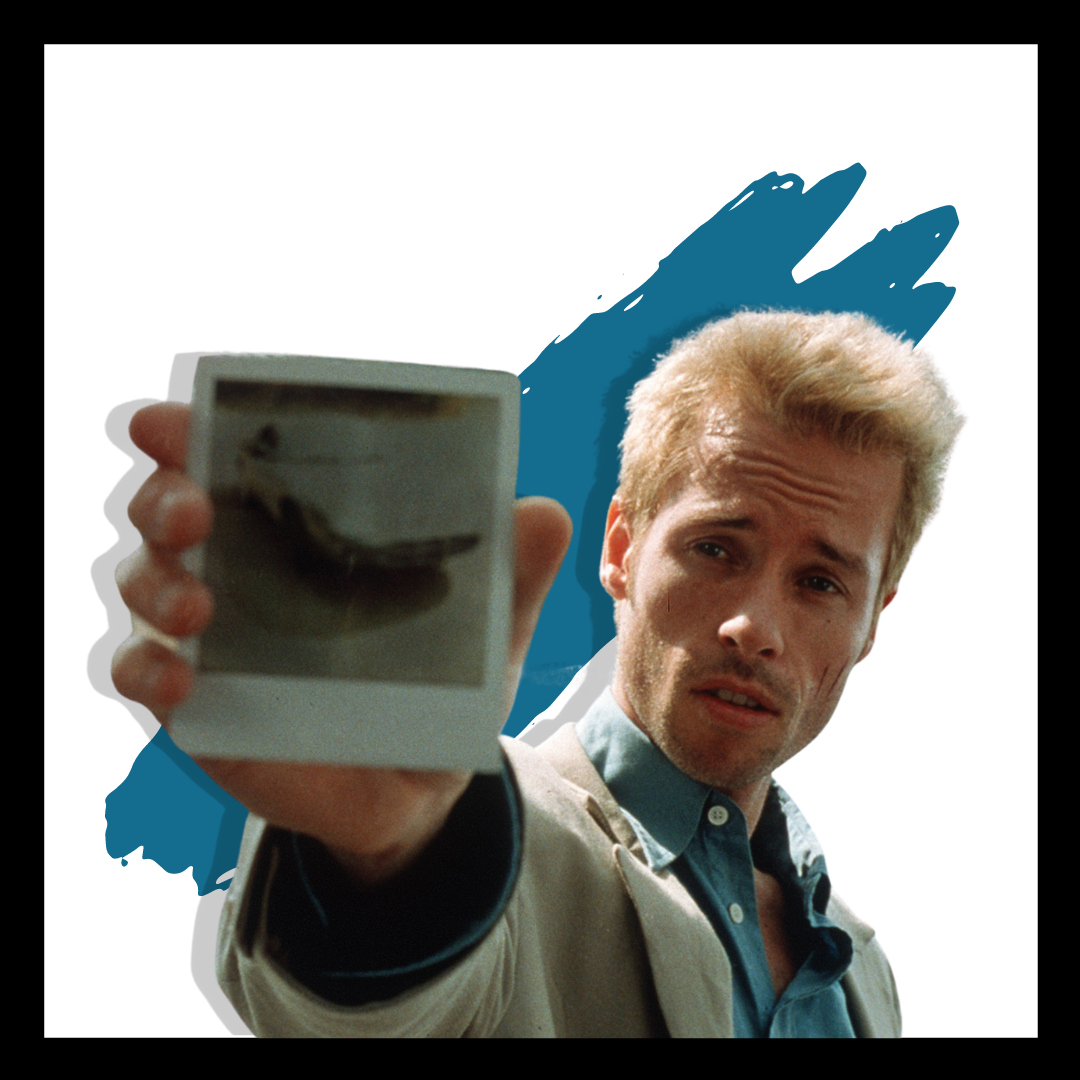

Christopher Nolan is a filmmaker who came from humble beginnings and eventually became one of the biggest names in Hollywood. If you want to know more about how Nolan came to be, check out last week’s blog post. This week we will be taking a deeper dive into Nolan’s writing process, specifically looking at the script for his Oscar nominated movie, Memento.

I’m sure we’ve all heard the modern day tales of Christopher Nolan having to print his screenplays on red paper to avoid people trying to steal his ideas, but at the time that he wrote Memento, this probably wasn’t of concern to him. In years prior, Nolan had only written and directed a few shorts and an 86 page screenplay for an 80 minute movie called Following. Following had garnered minimal acclaim, but it certainly was not a contender at the Oscars. However, it was most impactful in that at 30 years old, it helped Nolan gain ample funding from producers to turn his next wild and unconventional idea into his second feature film, Memento.

Nolan’s idea for writing Memento came from an idea his brother had for a short story. On a cross country road trip from Chicago to Los Angeles, Christopher Nolan’s brother, Jonathan, explained the idea. It was the story of a man, who, in a brutal attack, lost his wife and gleaned a head injury that caused anterograde amnesia, or short term memory loss. In order to find whoever killed his wife and ultimately exact revenge, the man had to follow tattoos on his body and notes that he had left himself in order to solve the mystery, all whilst struggling with amnesia.

Following the road trip Christopher and Jonathan went off and wrote their stories how they each saw fit. Jonathan wrote the short story Memento Mori, which was ultimately published in Esquire magazine. Christopher wrote the screenplay for Memento.

From the start, Christopher Nolan knew that his film version of the story should be told in first person, better yet from the point of view of the main protagonist, Leonard. Through Leonard’s consistent voice overs, Nolan wanted the audience to be experiencing the story as Leonard was, with a sense of amnesia, not knowing who other characters were, how he knew them, or whether or not they posed a threat. Nolan took it a step further by creating a non-linear timeline, and this is where things start to get crazy.

In the film Nolan has two main periods being shown, one in black and white, the other in color. Throughout the story we jump back and forth between color and black and white sequences, denoted throughout the script as it shifts.

The idea of the black and white section is that it provides more of an objective view of Leonard. The voice overs are more like interviews from a present day mind asking the past and the timeline is chronologically going forward. The purpose is to supply the audience with some clarity through bits and pieces of information about the main character that aren’t solely from his amnesia ridden mind. Although, as the black and white sequences progress, they become increasingly less objective, and more in the mind of Leonard as he exists in this particular timeline.

The color sequence, on the other hand, is intended to provide a subjective view of the story. The voice overs are specifically Leonard at that exact moment in time, showing the audience what he is thinking as he is thinking it. Dissimilar to the black and white sequences, the color scenes are on a reverse chronological timeline. These scenes move backwards in time from a point later in the film to somewhere in the middle. In contrast to the black and white, which alternates from objective to subjective as the film progresses, the color sequences change from subjective to a more objective view as the story comes to a close. Besides these two timelines, there are also periodic flashbacks to a time even further back that provide even more context (as well as confusion). Although one is going backwards in time and one forwards, the color and black and white timelines meet at the end of the movie at a point somewhere in the middle of Leonard’s story. This is because the color has moved backwards from some point in the future while the black and white has moved forward from some point in the past. Albeit hard to wrap your brain around, the execution of this perplexing idea is ingenious.

Taking a closer look at the script itself, a separate entity from the brainstorming and ideation process, it is no wonder that Nolan was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Screenplay.

First, the aforementioned timeline is seamlessly integrated into the written word. Nolan is careful to keep the timelines separate through varying textual indicators like font and color. This way, whether using it while directing, or as an outsider reading it as a piece of text, it is very clear what part of the story we, and the characters, are in as the script progresses.

Another aspect of the script that is notable is Nolan’s superb dialogue and use of voice overs in order to illustrate the confusion and reality-twisting nature of Leonard’s amnesia. First and foremost is the dialogue between Leonard and other characters. Nolan has the perfect balance of providing pertinent information to the audience and Leonard, while also maintaining mystery and a vagueness that keeps you on your toes, wondering what the context is to their words and how it plays into the bigger narrative.

In conjunction with dialogue from other characters, Leonard’s voice-overs and internal monologues are a guiding force throughout the entire film. The perfect example of this interplay is in the first few pages of the script. Leonard wakes up and his voice overs immediately begin as he tries to figure out where he is and why he’s there. Following this questioning, Leonard meets Teddy, another main character, and is trying to figure out, internally and externally, through notes he’s left himself and through the conversation he’s having with Teddy, whether this is someone he can trust, or if this man had something to do with his attack and the rape and murder of his wife.

Beyond it being a genuinely well written script, and an enjoyable story to read, Christopher Nolan’s screenplay for Memento is the perfect example of someone breaking down expectations in order to tell the story he needed to tell. I’m sure a lot of people were weary about the complicated storyline, and I’m sure there were people that told Nolan this story could not be told this way, but Nolan stuck with his gut. He not only wrote the screenplay that he wanted to write, but also turned it into an Oscar nominated, $40 million box office hit.

If you are writing your story and struggling with the fear that you think the plot might be too outlandish, or people won’t understand, I urge you to feel the fear and do it anyway. You never know when taking the risk will pay off in ways you could have never anticipated.

Don’t give up on yourself or your stories and always be writing.

Read the Memento screenplay here.

Follow Hannah on Instagram: @hannahwagner3932

Always be writing.

Dream big.

Tell better stories.

Never give up.

Leave a comment